On 16 March, the European Commission published the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRM Act), a legislative proposal intended to strengthen the EU’s autonomy in the supply of key raw materials in the aftermath of Covid-19 and the energy crisis following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

The Act is meant to diversify the bloc’s sources of raw materials needed for green transition technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines. It was presented on the same day as the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA), the EU’s response to the U.S. major green subsidies package meant to improve the bloc’s competitiveness in innovative clean tech industries, and the reform of the electricity market design. This package of measures, announced in the Green Deal Industrial Plan, intends to create a conducive regulatory environment for net-zero industries and the competitiveness of the European industry overall.

Content of the Regulation

Scope of the Legislation

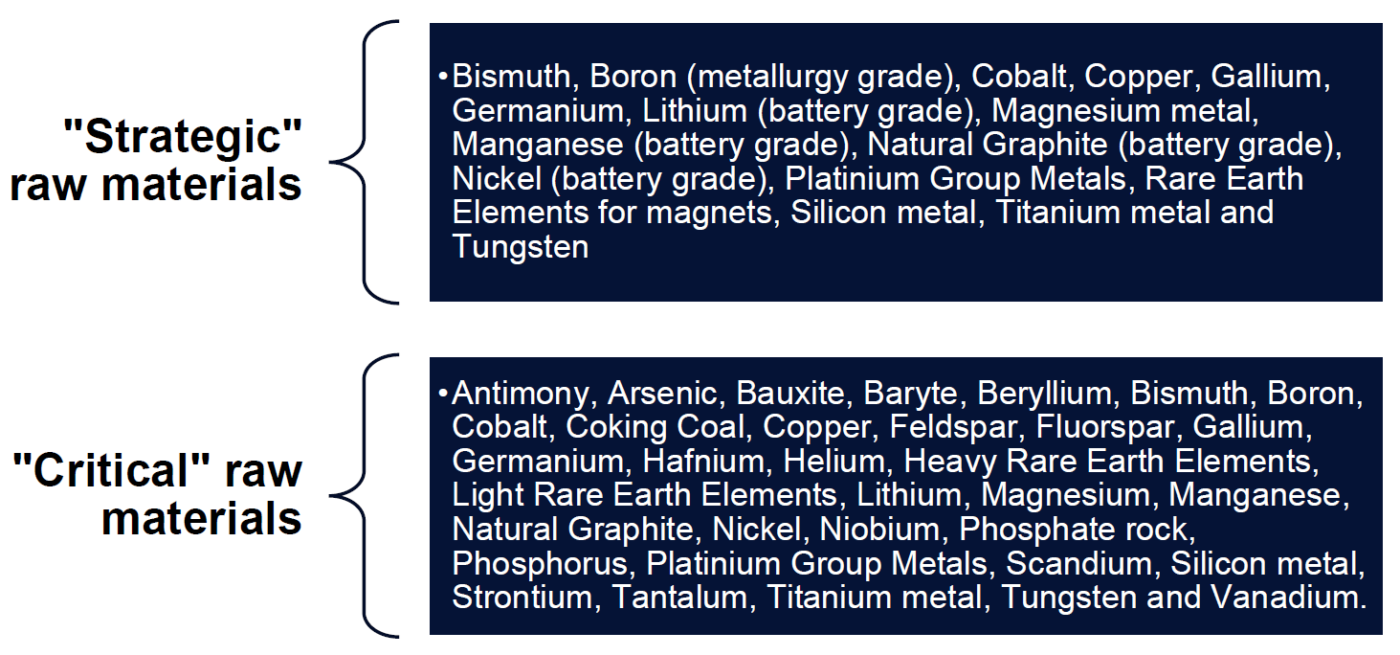

The Act will apply to materials deemed “strategic” (Annex 1) such as lithium, nickel and rare-earth elements used in magnets, as well as materials included on the revised version of the EU’s list of critical raw materials (Annex 2). The regulation embeds both lists, which will be updated at least every four years, in EU law.

Overall, "strategic" raw materials refer to resources whose current production is difficult to increase and for which the demand is expected to grow significantly in the long term due to the green and digital transitions as well as defence and space applications. The larger list of 34 "critical" raw materials includes the 16 selected “strategic” materials as well as materials that a shortage of could derail economic activity in the shorter term, as they are of high importance to the EU economy and difficult to obtain.

Main Targets

As these materials are a prerequisite for the success of the green and digital transitions, the Commission expects the consumption of such materials to increase many times in the next couple of years. Therefore, they have set three indicative targets for Europe’s self-sufficiency along the entire value chain for 2030:

- EU countries collectively should be capable of extracting at least 10 percent of the EU’s annual consumption of strategic raw materials.

- EU’s domestic processing of raw materials should cover at least 40 percent of the bloc’s annual consumption of each strategic raw material.

- The EU’s recycling capacities should account for at least 15 percent of its annual consumption of each critical raw material.

The Act also aims to improve the EU’s ability to monitor and mitigate the supply risks related to raw materials. Member States will be required to send a report to the Commission each year featuring information such as the state of their strategic stocks of these raw materials.

Circularity and Sustainability of Critical Raw Materials

The legislative proposal highlights the importance of increased efforts to mitigate any adverse impacts around critical raw materials supplies, both within the EU and in third countries with respect to labour rights, human rights and environmental protection.

Member States will be required to detail in a national programme the measures that they are taking to increase the collection, recycling and reuse of critical raw materials. However, these requirements are not the subject of any quantified objective. Member States and private operators will also have to investigate the potential for recovery of critical raw materials from extractive waste in current mining activities and from historical mining waste sites.

Additionally, large companies manufacturing strategic technologies in the EU which consume a significant amount of strategic raw materials will be asked to audit their existing supply chains, undergo a company-level stress test and develop strategies to be better prepared for supply disruptions.

The Commission also aims to consider the environmental footprint of products containing critical raw materials placed on the European market by making it an obligation to declare this footprint when entering the market. Products containing permanent magnets will need to meet circularity requirements and provide information on recyclability and recycled content.

Finally, among other measures, the proposal sets out rules for the Commission to recognise schemes, such as the one developed by the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), that certify whether materials have been extracted sustainably.

Dependencies Reduction

The EU is heavily dependent on importing raw materials it deems critical. Much of it is imported from China, which holds a quasi-monopoly on many of these critical raw materials.

To reduce the bloc’s reliance on single source countries, the Commission aims to “set a benchmark to not be dependent on one single third country for more than 65 percent of imports for any strategic raw material by 2030.″ With China controlling most of the value chains of many raw materials, such as copper, cobalt, lithium and others, the target is expressly designed to prevent potential supply shortages and to boost resilience.

The Act is also aiming to diversify the European supply chain by identifying strategic projects in third countries. Establishing strategic and mutually beneficial partnerships with third countries is considered essential to improving the EU’s security of supply. The EU has already included dedicated raw materials chapters in recent FTAs with New Zealand, Chile and the upcoming deal with Australia. The Commission has also been scrambling to seal new partnerships with countries like Canada, Ukraine, Namibia and Kazakhstan to diversify its supply chains. A European Critical Raw Materials Board (CRMB), which is yet to be established, will be responsible for monitoring the progress of these partnerships and identifying which third countries should be prioritised for the conclusion of such collaboration agreements.

The Commission intends to use its Global Gateway instrument, a €300 billion initiative aimed at countering the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, as a vehicle to financially support projects abroad. The Initiative will also assist partner countries in developing their own extraction and processing capacities, including skills development.

Strategic Projects

The CRM Act includes special treatment for projects that are deemed “strategic” by the Commission and the CRMB. Only strategic projects which are strengthening the EU's security of supply, are technically feasible and sustainable can be considered as having an "overriding public interest,” potentially allowing them to take precedence over EU environmental laws.

Similarly to what is planned in the NZIA, the proposal sets out a framework to select and implement strategic projects, both within and outside the EU, that would benefit from a more streamlined and predictable permitting process and additional funding. For example, the law would oblige each EU state to designate an authority responsible for permits, which would have at most two years for the permitting process for a strategic project involving extraction and at most one year for a project involving only processing or recycling. For projects that are already under consideration and that are not yet recognised as strategic, these durations are reduced to twenty-one and nine months respectively.

For additional financial support, the text states that “private investment alone is not sufficient” and adds that the “effective roll-out of projects along the critical raw material value chain may require public support” such as financial contributions from the European Investment Bank or Member States in the form of state aid. The recent revision of the EU’s state aid rules (i.e., the Commission’s new Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework) should simplify state aid rules for renewable energy deployments and for decarbonising industrial processes, including in the mining sector, by Member States.

Local community opposition to mining projects is another major obstacle to the development of these strategic activities. To address this issue, the Commission expects Member States to be able to help their companies “increase public acceptance” of these projects, which should be granted the status of the highest national significance possible.

The legislation also foresees a voluntary joint purchasing mechanism that would be open to EU undertakings consuming raw materials and relevant authorities in the EU countries responsible for stockpiling. The Commission's proposal calls it “a system to aggregate the demand” to be used for achieving “better conditions with their suppliers or to prevent shortages.”

Finally, the Commission wants to remedy its lack of information on the subsoil content by obliging each Member State to develop a national exploration programme. States should communicate these programmes and the progress of their implementation to the CRMB. Mining companies currently in operation will have to submit a preliminary economic assessment of the content of their mining waste in critical raw materials.

Critical Raw Materials Club

The Commission also published on 16 March a non-binding Communication outlining its plans for a Critical Raw Materials Club of like-minded trade partners, among other measures. The Commission wants to team up with international partners to secure access to critical raw materials as a counter to China’s dominance in critical raw materials supply chains.

The EU hopes that this club could be used as an avenue to soften transatlantic friction over U.S. subsidies for green tech. It would involve the U.S. granting a free-trade deal status to certain imports using raw materials, without there being an actual trade deal in place with the club’s member countries.

In exchange for granting these concessions to the Europeans, the U.S. could use this club as an additional platform to encourage “like-minded” countries to reduce their reliance on China. The club would also build on an agreement struck on 10 March between the EU and the U.S. to launch a targeted critical minerals agreement.

Next Steps

The CRM Act will now be reviewed separately by both the Council of the EU, representing Member State governments and the European Parliament according to the ordinary legislative procedure. This proposal has been waited for by the Council and is also strongly pushed by Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton.

While this file is likely to be prioritised by the EU institutions and Member States given the current geopolitical context including the IRA pressures, we can expect the legislative process to be delayed in the Parliament as many committees will want to get involved (e.g., internal market, environment, trade, transport committees) and MEPs will likely call for stricter environmental provisions. However, Pascal Canfin (Renew Europe, France), the chair of the environment committee, recently stated that he expects a strong majority in Parliament for the slate of upcoming green industry legislation, with a goal to close a final deal on the CRM Act in Parliament before the end of the year.

At the Member States’ level, the file could become contentious when it comes to concrete regulatory measures as countries are already emphasising different aspects of the Act. We expect Spain for example, which will hold the Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2023, to focus primarily on speeding up permitting procedures and trade diversification with Latin America. It might, therefore, be complicated to get this file out of the door before the May 2024 European Elections. The EU 27 leaders will discuss the NZIA and the CRM Act at the next European Council Summit on 23 and 24 March.

Early reactions to the draft regulation include industry bodies broadly welcoming the initiative, whereas NGOs raising concerns mainly related to the feasibility of the targets and potential conflicts with environmental legislation.