Despite the popular notion that the outlook for trade negotiations between the United States and China is gloomy, there may be room for cautious optimism that a positive outcome benefitting multinational companies can ultimately be achieved. Companies and executives evaluating their business strategies in China should focus on staying the course and avoid making major strategic shifts based on the short-term fluctuations. In short, there may be light at the end of the tunnel.

President Donald Trump’s unilateral approach has undoubtedly created some self-inflicted damage to U.S. companies and the U.S. economy, and companies are justified in their concerns over the harsh rhetoric and escalations since the first tariffs were implemented in early 2018. Trade tensions have cast a cloud of uncertainty over the business environment, which has made decisions on future investments extremely difficult. Speculation over possible efforts to “decouple” the world’s two largest economies has increasingly been a cause of concern for companies that rely on supply chains in China.

Nevertheless, companies should strategically position themselves to benefit as much as possible if a trade deal is reached. Large-scale de-coupling remains unlikely, and both Washington and Beijing have indicated that they recognize what is at stake if they fail to reach an agreement. Furthermore, over a dozen rounds of talks through the end of 2019 have established a basis for continued dialogue between the two countries that could potentially lead to an agreement being reached.

Even though the talks have not yet yielded an agreement, there have been periods of sustained momentum, including a period in early 2019 when it appeared a deal might be in reach. Despite the breakdown in negotiations in May 2019, talks up to that point helped produce a 150-page document which can be drawn upon to re-build a framework for a deal that both sides can present to their constituents as a victory. Even an imperfect deal would produce tangible benefits for multinational companies in China.

If the two sides are ultimately able to reach a deal, the timing of any agreement will likely be dictated largely by political factors and the state of the U.S. economy. As the 2020 U.S. presidential election approaches, Trump might find it politically beneficial to keep the trade war with China “open” as long as possible. Trump might seek to hold out on making a deal for as long as he can, so far as the U.S. economy does not falter too much, before seeking to strike a deal shortly before the election. Doing so would give him a boost ahead of Election Day and leave critics with too little time to pick apart the deal or gather evidence if China does not follow through on aspects of the agreement.

Evolution of the Trade War

In looking back at the first three years of the Trump administration and its approach to China, it is important to bear in mind that even if a more traditional candidate such as Hillary Clinton or Jeb Bush had been elected in 2016, they too would have likely taken a tougher approach towards China, especially on trade and economic issues. Trump’s approach towards China, however, has been stylistically very different from the approaches that other more traditional candidates might have taken. He has rejected working with allies, building coalitions, and leveraging multilateral frameworks, and instead relied on a unilateral approach and applying consistent pressure through tariffs and rhetoric. However, while his approach may be distinct stylistically, it is important to note that there was already a growing consensus in Washington prior to Trump’s election that the U.S. needed to take action to address longstanding grievances on trade and economic issues.

Early Stages and Tariffs

The roots of the ongoing trade conflict can be traced back to promises Trump made on the campaign trail in 2016, when he claimed that China’s entrance into the World Trade Organization enabled the “greatest jobs theft in history.” For much of his first year in office, Trump was initially transfixed by the U.S. trade deficit with China, which he would eventually use as the main justification for implementing the first rounds of tariffs in early 2018. While some in Washington disagreed with Trump’s view that the trade deficit should serve as the rationale for implementing tariffs, there was growing consensus that issues related to China’s unfair trade practices needed to be addressed.

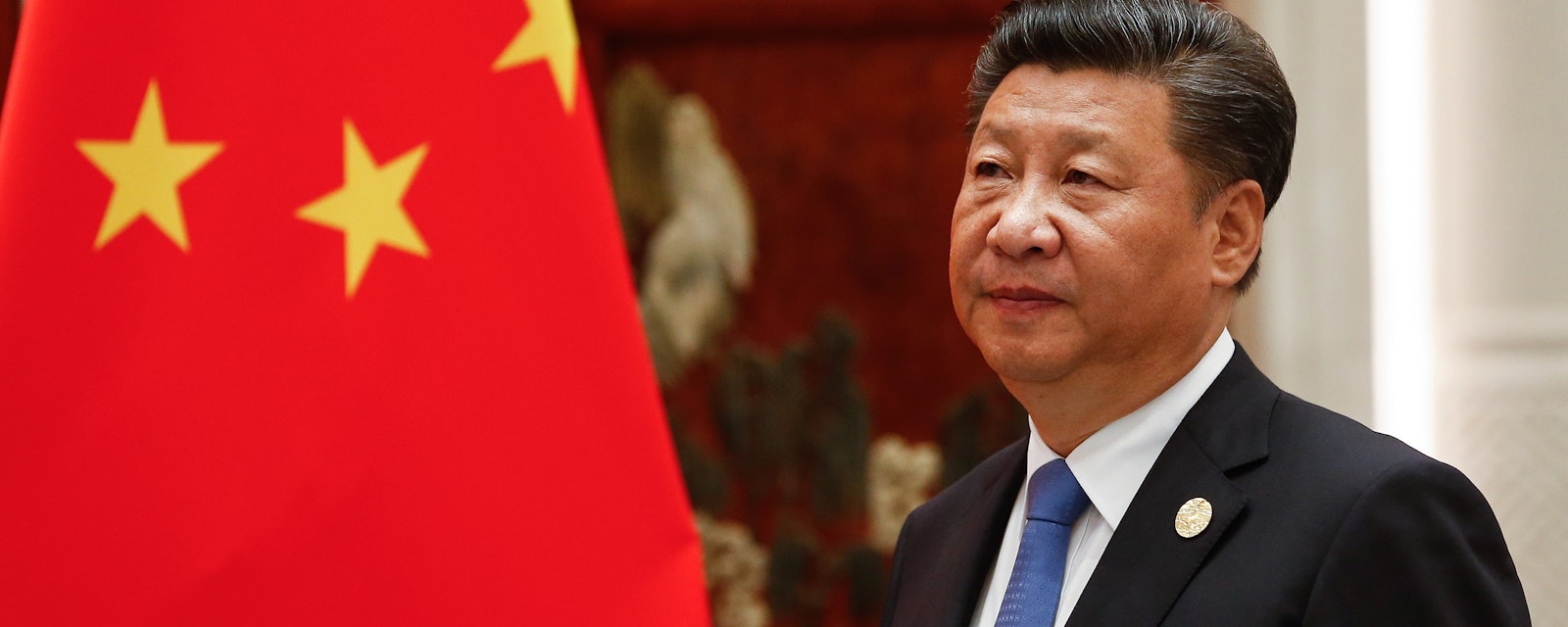

A meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago in April of 2017 signaled that the two leaders recognized the need for negotiators from both sides to sit down and engage in talks. Despite Trump’s harsh campaign rhetoric towards China, Trump left the meeting touting the “great chemistry” he had with Xi. Trump continues to emphasize the strength of his “friendship” with Xi insofar as he can use their personal relationship to help soothe markets and alleviate concerns that U.S.-China relations could completely fall apart.Trump and Xi’s personal relationship could only stave off growing frustration in the U.S. for so long. Shortly after the start of his second full year in office, Trump began implementing tariffs on a range of imported goods, including several major imports from China. China responded with retaliatory tariffs in April 2018, prompting Trump to announce plans for 25% tariffs on $50 billion of Chinese imports only one day later. China responded in kind by revealing its own plans for tariffs on $50 billion in exports.

A pivotal moment in negotiations occurred during the spring of 2018, when Trump initially accepted, but then rejected, a preliminary Chinese offer centered mainly around the purchase of more U.S. goods. Trump’s decision to reject the offer was largely a result of backlash in Washington over the idea of reaching an agreement based on purchases with little or no progress on structural issues.From that point on, Trump has recognized that in order to effectively sell the deal at home, he will have to achieve some degree of progress in resolving issues such as intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, and nontariff barriers, in addition to bringing China’s industrial subsidies and support for state-owned enterprises in line with World Trade Organization guidelines.

Tit-for-tat escalations continued until December 2018, when Trump and Xi agreed on a 90-day ceasefire on the sidelines of the G20 in Buenos Aires. Despite the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Canada (at the request of the U.S. government) on the same day Trump and Xi met in Argentina, positive signals in early 2019 offered a glimmer of hope after the two sides held seven consecutive rounds of trade talks over the span of four months to start the year. As momentum appeared to be building towards a possible deal, optimism spiked when China extended the suspension of additional tariffs on U.S. autos and auto parts and U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin claimed in April 2019 that the two sides had agreed to establish “enforcement offices” to monitor the enforcement of a trade deal. There was even growing speculation over the timing of a possible Trump-Xi meeting, as reports emerged that the negotiating teams were finalizing the text of a nearly 150-page draft trade agreement.

Negotiations, On and Off

An abrupt turn of events in late April of 2019 provided a reality check for both sides and revealed the complexity of the challenges that both Xi and Trump face in trying to reach a deal. Hopes that the two sides were on the verge of announcing a deal came crashing down when Trump issued two harshly-worded tweets on May 5th threatening to raise the tariffs rate to 25% on $200 billion of Chinese goods. The escalation scuttled plans for Chinese negotiators to travel to Washington for the next round of trade talks, dashing hopes that the trip could help stabilize to the situation.

There are indications that the collapse in talks occurred primarily due to pushback on the deal from within senior political levels in China. The two sides negotiated the terms in English until the document was finally translated into Chinese in late April and presented to members of China’s Politburo after there were already reports out that significant momentum had been building towards a deal. When certain members of the Politburo viewed the complex terms of the document in Chinese for the first time, however, they felt the draft agreement was too one-sided and that some of the U.S. demands amounted to a violation of China’s sovereignty. In response, the Chinese side sent back a heavily revised document to their American counterparts. This has been interpreted by the many on the U.S. side as a classic negotiating tactic by the Chinese, but there are indications that it is more a function of President Xi running into significant internal politics of his own in China with a number of Chinese officials fearing the U.S. goal is to dupe China into signing a one-sided and unequal agreement.

The U.S. followed through on the tariff hike on May 10th, prompting China to retaliate by raising tariffs on US$60 billion worth of U.S. goods. After the U.S. Department of Commerce effectively blacklisted Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd by adding the company and its affiliates to its “Entity List,” China’s Ministry of Commerce announced it would be establishing an “unreliable entities list” of foreign companies, individuals and organizations that “do not follow market rules, violate the spirit of contracts, blockade and stop supplying Chinese companies for noncommercial reasons, and seriously damage the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese companies.”

Attempts to Rebuild Momentum

The resilience shown by the two sides in getting back to the negotiating table after the May 2019 collapse in talks serves as an indication that both countries might ultimately want, and in many ways may need, a deal. A meeting between Trump and Xi at the G20 in July produced only a temporary ceasefire. After trade talks in Shanghai in late July yielded little progress, Trump lashed out on Twitter on August 1st, announcing new tariffs to take effect starting in September. Escalations continued when the U.S. Treasury Department declared China a currency manipulator several days later.

However, Trump eventually decided to delay some of the tariffs he announced on August 1st in order to avoid taxing consumer goods during the peak holiday shopping season. As plans were made to resume talks in October, the two sides expressed a desire for de-escalation and an eagerness to get back to the negotiating table.

Three ‘Going Forward’ Scenarios

A ‘no deal’. The chances of “no deal” scenario is unlikely because such an outcome would be bad for the economies of both countries. A protracted trade conflict could restrict China’s access to U.S. technology and slow China’s economic growth. For the U.S., the costs of tariffs for consumers will rise considerably if the U.S. follows through on all the tariffs that were announced on August.

A comprehensive deal.

Even less likely than no deal, is a comprehensive deal, that achieves many or all of the core demands initially outlined by U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and his negotiating team on structural issues such as intellectual property protection, forced technology transfer, and nontariff barriers. The breakdown in negotiations in May 2019 made it apparent that expectations on the U.S. side that China would agree to change its laws as part of the deal while also agreeing to allow the U.S. to leave tariffs in place as an enforcement mechanism will be difficult for the Chinese side to accept. Allowing the U.S. to impose its will on China would make Xi appear weak and undermine the credibility of his leadership. Xi has gone to great lengths to establish himself as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, and will not accept any deal that calls into question his ability to stand up to Trump and aggressive actions by the U.S.

A partial deal.

The most likely of these three scenarios is a partial deal that includes some purchases, removal of some or all tariffs, and some action on the structural issues – particularly reforms that could be beneficial to China. There is a recognition among many policymakers in China that reforms which provide a greater role for the market are the only path for continued growth and development. Reforms announced at the Third Plenum in 2013 have long since stalled out, and prior to the breakdown in talks in May 2019 there was a growing optimism among many Chinese decision makers that pressure from Trump could push China to jump-start these reforms. If the two sides can make concessions and strike the right balance, there is a chance that a “win-win”

solution can be achieved.

Pressures at Home and Abroad

Aside from the trade conflict, Xi has his hands full dealing with a complex set of issues at home. In particular, the situation in Hong Kong poses a major threat to Xi, who has called on officials to maintain a “fighting spirit” in the midst of the challenges that the Chinese leadership is facing. There is belief among some within the Chinese leadership that Xi’s consolidation of power contributed to the government’s misreading of the scope of discontent in Hong Kong.

Perhaps the greatest risk that the situation in Hong Kong poses for Xi is that it could exacerbate discontent and discord within the Chinese leadership over other issues. In Taiwan, the unrest in Hong Kong has boosted the reelection chances for incumbent President Tsai Ing-wen, whose Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) favors independence over strengthening ties with Beijing. In Xinjiang, China’s repressive policies and the mass detention of ethnic Uighurs and other Muslims have drawn international condemnation. All of this is happening as China’s economic growth continues to slow, while the expectations of the Chinese people for improved standards of living continue to rise.

Pressure From the International Community on China

The U.S. is not alone in responding to China’s growing influence on the international stage. As the trade war between the U.S. and China has escalated, American allies in Europe and Asia are also recalibrating their

approach to China. In March 2019, the European Commission released a report titled “EU-China – A Strategic Outlook,” labeling China as a “strategic partner,” “economic competitor,” and most notably, a “systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.” The release of the report preceded a visit by Xi to Italy and France that highlighted the growing divide in Europe over China’s increasingly assertive push into the region. Beijing’s growing economic investment through Xi’s signature foreign policy objective, the Belt and Road Initiative, and diplomatic initiatives like the 16+1 Forum are raising worries by U.S. allies over the implications of Beijing’s rising involvement in the region.

In the Pacific, Australia is also taking steps to respond to China. Australian officials often point out that Canberra was the first to ban Huawei and ZTE from providing 5G technology on national security grounds in August 2018. Australia has also expressed concern over China’s expanded political influence operations, including steps to ramp up cultural and educational soft power, boost aid programming, upgrade efforts to influence politicians and political parties abroad, and adopt a more assertive approach to shaping global narratives about China and about China’s developmental model. Canberra has even enacted legislation to prevent Chinese interference in their domestic politics.

The European Union and Australia have taken clear but measured steps in responding to China’s growing influence. They also continue to seek out cooperation – especially in their economic ties – where it is still mutually beneficial but are also standing firm where they believe that Beijing is undermining their interests. The U.S. may be creating the most noise in pushing back on China, but policies emanating from Brussels and Canberra demonstrate that Washington is far from alone.

The 2020 Testing Grounds

Just as Trump faces domestic political considerations heading into 2020, so does Xi. The same internal politics that led to the collapse of talks in May 2019 will remain a major factor in China’s approach to the negotiations. Xi needs a deal that he can demonstrate does not equate to China acquiescing to U.S. demands, but rather one that achieves a resolution to the conflict in a way that conveys the strength and confidence of an increasingly powerful China.

Adding a layer of complexity to Xi’s dilemma is the fact that he is facing pressure not just from the U.S., but also from important U.S. allies in Europe and the Asia Pacific. These countries are recognizing and responding to increasingly assertive actions taken by China – albeit in a much less dramatic way than Trump has done since entering office. After spending much of his first term in office consolidating power, Xi is now facing his toughest test yet.

Major flashpoints remain and should be monitored closely in the year ahead.These include the ongoing Hong Kong protests, a general election in Taiwan in early 2020, and the extradition hearings for Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, which begin in January 2020 and are expected to continue until October. The passage of the bipartisan Uighur Human Rights Policy Act by the U.S. Senate, along with calls from U.S. lawmakers for the Trump administration to apply Global Magnitsky Act sanctions on Chinese officials involved in the Xinjiang crackdown could lead the U.S. to take action on human rights abuses in China. Tensions between the U.S. and China could also flare if Congress eventually passes the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act. Additionally, the potential for unintended confrontations in the South China Sea between U.S. and Chinese warships presents a persistent threat to the bilateral relationship and could impact trade negotiations if a major incident occurs.

In the longer-term, the next major battleground will be over the development of next-generation technology. A trade deal that involves compromise on both sides could be a crucial first step in stabilizing the relationship and steering the two countries away from rivalry and zero-sum approach to competition. Multinational companies should prepare for on-again, off-again tension and conflict between the U.S. and China for the foreseeable future, while also maintaining their commitment to the Chinese market.

Recommendations for CEOs and Executives

The trade war has created a complex set of geopolitical challenges for companies operating in China. In order to avoid getting caught in the crossfire between the two countries, multinational companies should maintain close coordination with their government affairs teams on the ground and should carefully evaluate their existing partnerships in China. Ensuring full compliance with regulations is crucially important, especially as China prepares to launch its new “Unreliable Entity List,” and as it plans to roll out a “social credit” system for both Chinese and foreign companies in 2020.

CEOs and executives should seek out opportunities to travel to China, while also being mindful of risks related to travel for Chinese-foreign dual citizens who have not undergone the necessary procedures to formally revoke their Chinese citizenship, as China continues to treat any Chinese citizen as such unless the person actively relinquishes his or her Chinese identity documents. Visits to China can serve to both demonstrate companies’ commitment to the Chinese market and help CEOs and executives gain a greater sense of the situation on the ground. Key Chinese government-sponsored conferences and dialogues such as the Bo’ao Forum for Asia, China Development Forum and World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting of the New Champions all provide excellent opportunities for CEOs and executives to engage with important stakeholders.

Stakeholder engagement in China, however, should not be limited to meetings to government officials. Frequent engagement with leaders in business, academia, and media can help cultivate relationships that enable CEOs to gain a greater sense of the business environment from the perspectives of influencers who impact policy and decision-making in their respective industries.

Finally, it remains critically important that foreign companies demonstrate alignment with China’s national economic and development objectives, including efforts such as urbanization, food safety, poverty alleviation, environmental protection, and sustainable development. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is currently in the process of drafting China’s 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which will be approved by China’s top legislature in early 2021. The 14th FYP will be an important blueprint outlining the government’s top objectives for the period from 2021 to 2025, and sectoral and regional plans will be made based on its principles and targets. Multinational companies with long-term growth strategies in China must possess a comprehensive understanding of important policy documents such as the 14th FYP and should seek out opportunities to support the goals they outline.