To date, Covid-19 infections and deaths have bucked initial worst-case expectations, but limited testing might mean the pandemic’s impact is grossly underestimated. While many governments continue to pursue relatively cautious public health strategies, growing variation is evident. Pressure for exit strategies is intensifying rapidly across the continent, but easing measures will increasingly differ in terms of speed and extent.

Behind the Curve

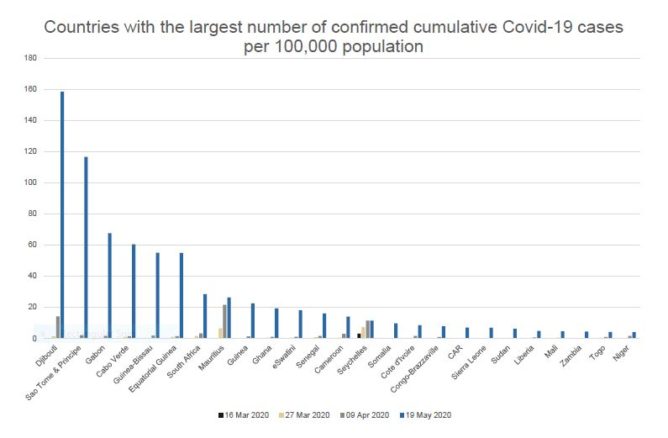

As of 19 May, a cumulative 60,066 Covid-19 cases had been reported across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with 1,389 deaths (see graph 1). South Africa remains the worst affected country, with 16,433 cases and 286 deaths reported as of 19 May. However, as evident from the second graph, small countries in terms of geography and population have the highest infection rates per 100,000 of population, though this could be because it may be easier to test larger segments of the population in these states. As a proportion of the population, Nigeria’s incidence ranks very low, but this could at least partly be due to limited testing. In fact, Nigeria appears to have done the least testing in the region (0.17 tests per 1,000 people), whereas South Africa (7.77) and Ghana (5.52) have carried out the most tests in the regional context.

Countries that moved early on containment and testing – Ghana, Senegal and South Africa – are considered the more successful examples of governments’ pandemic responses on the continent. In particular, Ghana’s pool-testing system, under which around 200,000 people have been tested, has reportedly enabled officials to identify infection hotspots around Accra and thus provided a head-start on contact-tracing.

For now, the overall pandemic picture is better than it has been in badly hit regions like Europe, both in terms of infection curves and fatality rates, though there remains significant uncertainty over this data in most countries. According to the British Medical Journal, projections of the percentage of the population likely to be infected on the continent have been revised downwards, to about 22%. The WHO’s latest expectations for the continent also seem more optimistic. WHO Africa Director Matshidiso Moeti has cited new evidence from the continent suggesting that – while the virus will linger for several months, if not years – it may infect and kill fewer people than elsewhere. One important factor in the outlook could be demographic factors, particularly SSA’s young average population age. Notwithstanding major concerns over testing capacity, comparatively favorable infection and mortality trends to date appear to be at least partly the result of early preventive measures, including lockdowns and travel restrictions.

Pandemic Response

As of 14 May, nearly 60% of African countries had adopted some form of pandemic measures, be they movement restrictions, social distancing, public health measures, governance and socio-economic measures, or lockdowns. By far the most common measures adopted by governments across the continent have been movement restrictions (including international flight suspensions in 45 countries, and partial border closures and domestic travel restrictions in 43), as well as social distancing measures, and isolation and quarantine measures. While most lockdowns (in 31 countries) were partial, including night-time curfews, three African countries have maintained full lockdowns. That includes South Africa, which has implemented what is considered one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. Despite the country’s reduction of its risk level from “5” to “4” on 1 May, the current restrictions still imply a much stricter regime than in many other countries.

By contrast, Nigeria has steered clear of a nationwide lockdown. Instead, it maintained localized lockdowns in Abuja, Lagos and Ogun State, plus some other state-level measures, from 30 March until 4 May. Since then, Nigerian authorities have switched to inter-state travel bans and overnight curfews, but have introduced a full lock-down of Kano State, which had emerged as a new infection hotspot. These measures will remain in place at least until 1 June. This is similar to Kenya’s approach. There, President Uhuru Kenyatta has extended a night-time curfew until 6 June, despite a relatively low infection rate with 912 cases. On 17 May, Kenya also closed its borders with Somalia and Tanzania, where the public health response has been almost entirely lacking and – in the case of President John Magufuli – utterly irrational.

Exit Strategies

However, across the board, the pressure to expedite exit strategies is intensifying by the day. The main drivers include the impact on hard-hit economies and precarious debt problems. According to the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), one month of full lockdown across Africa would cost the continent about 2.5% of the region’s annual GDP, or about USD 65.7bn, while companies in SSA surveyed by UNECA report operating at just 43% capacity. Also contributing to the pressure for exit strategies are the devastating implications for livelihoods and outright hunger (70% of slum dwellers report that they are missing meals or eating less due to the pandemic); public anger over abusive policing; and unpopular quarantine facilities (which are frequently dodged, for example in Kenya, given poor conditions).

Another factor is that even the public health efficacy of extremely strict lockdowns or curfews is increasingly being questioned. A case in point is South Africa. While the country’s lockdown is considered successful in flattening the curve, the reproduction rate has not dropped below one despite the strictest of measures. This particularly applies in the Western Cape, which is now South Africa’s worst affected province. As a result, and in keeping with evolving international experiences, smarter, longer-term measures that allow the greatest possible extent of economic activity are increasingly being demanded.

Here, governments’ approaches are likely to vary increasingly. For example, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire have eased some restrictions in their major cities and have focused instead on containing the spread between subnational regions. Meanwhile, South Africa remains under heavy Level 4 restrictions. Ramaphosa is coming under immense pressure from business, labor and increasingly scientists to loosen the lockdown. A further tweaking of some seemingly irrational Level 4 restrictions is expected, and business is pushing hard for a reduction to Level 2 as soon as possible. However, badly hit urban areas (Cape Town, Johannesburg, eThekwini and Nelson Mandela Bay, where South Africa’s Department of Health expects infections to peak only in another three months’ time) will likely face tougher restrictions for longer.

One major question for all markets is how well-equipped they are for a reopening without risking a surge in cases. WHO officials have cautioned that stronger containment measures – particularly contact tracing – will be required to stop widespread community transmission and ease the pressure on chronically strained health systems.