There are a host of elections across the region in 2018, led by Brazil and Mexico. Populism will remain a viable electoral offering but the risks posed by populist candidates should not be exaggerated. Electoral noise and blackspots of political turbulence will not detract from positives, including: an ongoing if uneven anti-corruption push, support for trade openness, and an improving economic outlook

LATAM 2018 Elections And Transitions

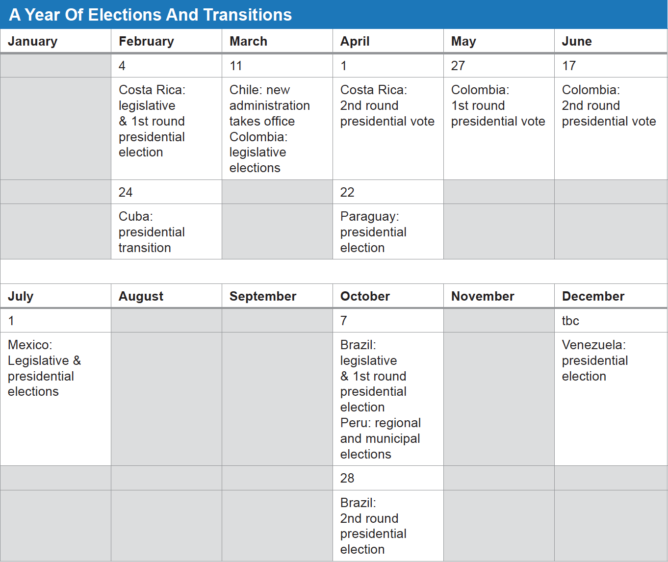

1. A Year Of Elections And Transitions

Apart from the sheer number of votes, what is striking is how open the outlook is in so many of these elections. The most immediate example is Chile, which holds its run-off presidential vote this Sunday, 17 December. Former president Sebastian Pinera (2010-2014), favorite for the duration of the campaign, is no longer a surefire bet to receive the presidential sash from Michelle Bachelet next March. In Brazil, former president Luiz Inacio ‘Lula’ da Silva (2003-2011) could yet be barred from running, while the center remains divided and crowded. Sao Paulo Governor Geraldo Alckmin has secured the endorsement of the centrist Social Democrats (PSDB), yet the party is badly weakened and he has slid in the polls. Anti-corruption crusader Marina Silva says she will mount a third presidential bid. Sao Paulo Mayor Joao Doria and Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles are two other possibilities. Such a fractured field makes it easier for Lula and the right-wing populist legislator Jair Bolsonaro to rally their bases, clear the first round of the election, and enter the run-off.

In Colombia, there are a dozen potential candidates with a shot at succeeding President Juan Manuel Santos. Mexico may not offer so many possible winners, but the presidential race is still remarkably open. Two candidates – Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador of the National Regeneration Movement (Morena) and Jose Antonio Meade of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) – will probably end up dominating the campaign, but since they will be offering two very different visions, uncertainty will dominate the first half of next year.

Cuba offers a different type of uncertainty; its leadership transition will be highly controlled, and the system will remain under Raul Castro’s tutelage for some time to come. But 2018 will see a historic transition away from the Castro leadership, most probably to First Vice-President Miguel Diaz-Canel, at a time of huge economic pressures facing the regime.

2. Red Herrings

Although support for democracy has dropped and there is widespread frustration with corruption, many leading populists are not as powerful or radical as they might seem. Despite ruling as a pragmatist during his first term, Lula has radicalized against the economic reforms championed by President Michel Temer. A court case in late January will likely bar Lula from running due to corruption charges. Yet Lula may still be able to run while appealing the decision to the Supreme Court. The more viable candidate is Bolsonaro, who has risen to prominence thanks to his ultra-conservative social views and economic nationalism.

Should either end up president, they would likely moderate their economic stance. Despite his rhetoric, Lula realizes the need for deep macro-economic reforms, particularly since pension reform under Temer is no longer viable. Bolsonaro, meanwhile, has already begun making overtures to the business community to win support from the center. It is likely he would pursue market-friendly reforms should he win. The larger risk post-2018 is the one already plaguing the country: that of a fickle Congress running amok on the watch of a hapless president.

In Mexico, even if Lopez Obrador wins, he is unlikely to enjoy anything close to a legislative majority. Lopez Obrador’s economic team is mostly made up of pragmatists, and a complete reversal of structural reforms is unlikely. In fact, a more troubling scenario may emerge if Lopez Obrador is narrowly defeated and/or there are signs of electoral fraud followed by a prolonged political dispute. Finally, in Colombia, former Bogota mayor and leftist Gustavo Petro, who leads some polls at this relatively early stage of the race, is the main anti-establishment candidate. However, Petro’s appeal beyond a left-wing hardcore is limited.

3. Bright Spots And Opportunities

There will be bright spots and opportunities across the region. Economic growth is set to pick up from this year, even if it remains below global growth rates. Elections will, on the whole, demonstrate how robust electoral institutions have become. There will be exceptions to the rule: Honduras is still mired in crisis after the November presidential vote, while in Bolivia, President Evo Morales is set to use 2018 as preparation for yet another re-election. Venezuela will remain in crisis in 2018; barring a new wave of massive unrest that prompts the armed forces to withdraw their support for the regime (unlikely), President Nicolas Maduro will most likely bully and cheat his way to re-election.

However, public demand for greater transparency following major corruption scandals this year will keep corruption on the agenda across much of the region; the political ramifications of judicial investigations may continue to create political waves, especially in Peru (where President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski may not hold on for much longer as president), but it will also help clean up the often-shadowy nexus of politics and business. On trade, a framework agreement between the European Union (EU) and the Mercosur trade bloc could finally materialize after missing the 2017 closure target.

At the country-specific level, Argentina will continue on the road to normalization. In Brazil, the Temer administration will continue to pursue limited economic reforms in areas such as energy. NAFTA’s uncertain future is a source of concern, but the issue has at least forced Mexican policymakers into a long-overdue drive to diversify trading relations; even if NAFTA collapses, Mexico would still enjoy Most Favored Nation status with the US. In Colombia, even if Uribisimo wins, the threatened tearing up of the peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) will not happen, while Ecuador will continue to transition away from former president Rafael Correa (2007-2017)’s brand of leftist lite-authoritarianism.