Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed may try to turn its military defeat in Tigray into a foreign relations advantage. The endgame in the conflict remains uncertain and bears risks for Ethiopia’s internal stability and even foreign disputes. While the onus is now on Tigray’s rebel leadership to declare a ceasefire, the Abiy government will be under pressure to avoid a regional blockade if it wants to avert the threat of broader foreign sanctions.

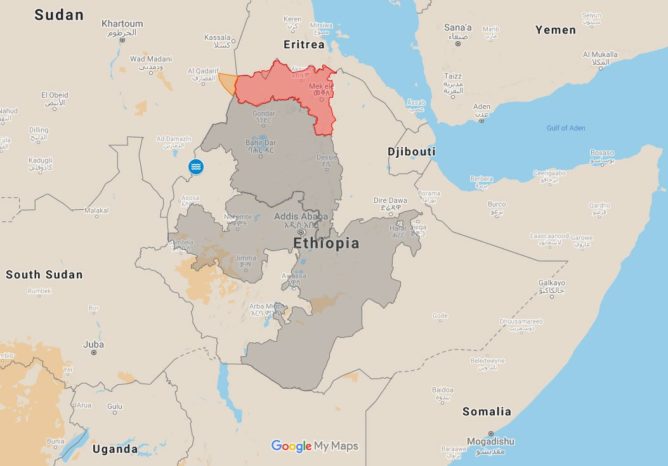

The Tigray conflict has taken a dramatic turn over the last two weeks as the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) began a counter offensive and retook the regional capital Mekelle and towns such as Shire. Reports that the TDF now controls a significant proportion of Tigray represent a stunning reversal of military fortunes in the eight-month-old conflict. An estimated 20,000 TDF fighters have been facing off against the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), Eritrean forces and Amhara militia, even though Addis Ababa’s large-scale deployment and drone strikes last November curtailed the TDF’s access to heavy weaponry and vehicles.

Equally game-changing has been Addis Ababa’s change of strategy. On 28 June, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared an immediate unilateral ceasefire for “humanitarian” reasons as ENDF troops were hastily withdrawing from Mekelle. To save face, the government threatened to retake Mekelle within weeks if needed, while the ENDF would now attend to a more significant “national threat” relating to the Sudanese border and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Although the effectiveness of the ceasefire (and fresh claims of Eritrean troop withdrawals) is still in question, it has increased pressure on the TDF to follow suit.

What Triggered the Change?

There is much speculation about the reasons behind Abiy’s change of strategy, but it is likely informed by changing calculations regarding the political, military, financial and foreign affairs costs of the war effort.

The TDF’s military advances appear to have played a major role. The TDF’s resurgence is not yet fully understood, but factors likely include the former ruling Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF)’s past insurgency experience (toppling the Derg regime in 1991); its capture of weaponry, food and medical support; and some preplanning for guerrilla warfare. Another factor is seeming popular support for the TPLF, which has been consolidated by atrocities attributed (not only but primarily) to Eritrean, Amhara and ENDF fighters. Even if federal forces could have held out longer in Mekelle, the asymmetrical war has seemed increasingly unwinnable.

Foreign pressure – particularly the prospect of deepening sanctions – probably contributed to the change of strategy. The Abiy administration might hope to gain a foreign relations advantage from its ceasefire declaration and thus mitigate the risk of broader sanctions. After all, a ceasefire and the withdrawal of Eritrean troops have been key demands from Western players.

Averting broader economic sanctions must be a key strategic goal for Abiy at this stage. He has conceded that 20% of the budget (USD 2.3bn) had already been spent on the Tigray operation, at a time when Ethiopia is seeking debt treatment under the G20’s ‘Common Framework’ process. Perennial liquidity challenges have worsened amid the war effort and the pandemic’s impact, though Ethiopia notably honored its 11 June Eurobond coupon payment.

Finally, the 21 June elections might have provided a political opportunity to change tack. Although the polls were not held in 20% of constituencies (including all of Tigray) due to insecurity and the results have been delayed until 9 July, Abiy’s Prosperity Party (PP) is widely expected to claim a strong mandate in parliament and the regional states. So far, the PP has won 50 constituencies in Oromia, while the regionalist National Movement of Amhara (NaMA) won two in Amhara.

What Next?

1) Threats to Stability

The biggest concern is that the developments could result not in a stalemate of sorts but continued conflict and/or an effective blockade of Tigray. Prospects for a ceasefire remain uncertain. The self-proclaimed Tigray government has threatened to drive its “enemies” out of Tigray. On 4 July, it issued its preconditions for a ceasefire, including calls for the withdrawal of Amhara and Eritrean forces to “pre-war territories”; accountability “proceedings” via an independent UN investigation; unimpeded aid access; and a restoration of all basic services. Tigray leaders further demanded what Addis Ababa may reject as de facto secession: the effective recognition of the “democratically elected” Tigray government as well as the resumption of budget transfers, while refusing any federal security forces entry into Tigray.

Two flashpoints reigniting the conflict would be 1) if the TDF tries to push Eritrean forces back into Eritrea and 2) if it tries to retake Western Tigray, where Amhara militia have taken over local administrations and repossessed land, annexing territory lost in 1991. The latter could have serious knock-on effects. A TDF push in Western Tigray could trigger a political backlash against the prime minister from his hardline Amhara allies (particularly in the context of NaMA electoral gains). Addis Ababa will also be concerned about the TDF/TPLF regaining access to Tigray’s border with Sudan, which could offer vital supply lines for an insurgent force otherwise encircled by hostile territory. Any Sudanese support for the TPLF – explicit or alleged – could prove explosive in the context of tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan, not only over the disputed al-Fashaqa triangle but also the GERD, where Sudan and Egypt are lobbying the UN Security Council to prevent Ethiopia from undertaking a second filling of the dam during the rainy season (starting mid-July).

By contrast, TPLF threats of marching on Addis Ababa (like in 1991) or invading Amhara region are likely overblown. Nevertheless, the Tigray situation will fuel separatism and secession demands not only in Tigray but in other regional states. While the TPLF has not traditionally pursued secession (unlike some Tigrayan opposition parties), it has now raised doubts about Tigray’s future as part of Ethiopia in the face of Addis Ababa’s “genocidal campaign”. Amid separatist sentiment, the degree to which the ENDF has been weakened by the Tigray war could also embolden insurgent groups elsewhere, like the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). The World Peace Foundation estimates that seven of the of 20 ENDF divisions have been completely destroyed and another three disrupted. This badly stretches federal forces needed to shore up federal authority in the Oromia, Southern Nations, Benishangul-Gumuz and Somali regions.

2) Blockade Concerns and Sanctions Outlook

One could argue that Abiy’s ceasefire announcement meets a key diplomatic demand, which, if credible, should reduce the threat of broader sanctions. To date, the US has imposed visa-related sanctions for Ethiopian and Eritrean officials and security force members “responsible for, or complicit in, undermining resolution of the crisis in Tigray”, as well as cuts in economic and security aid. For its part, the EU has suspended budget aid.

Yet the next bone of contention will be a feared siege of Tigray. Immediate humanitarian access is the top priority to prevent a famine of potential 1980s proportions. Up to 900,000 people are now facing famine conditions, of a total 5.2mn needing food aid. An important signpost will therefore be whether Addis Ababa restores a minimum of essential services –telecommunications, electricity, the airspace, the banking network, currency circulation and trade – to Tigray. To rebuff siege allegations, the Abiy administration may try to shift blame for disruptions onto the TPLF.

The most difficult political bridge to cross may be political dialogue – another key diplomatic demand. Direct dialogue remains challenging given that the Abiy government rejected the TPLF’s election of September 2020 and has since classified the TPLF as a terrorist organization. If talks were to happen, they would likely be secret initially. Diplomats may also push for a broader political dialogue beyond Tigray, to begin to address the grievances of other disenfranchised groups that together threaten to undermine Ethiopia’s stability.

All these obstacles highlight the risk of sanctions being deepened or at least maintained. Nevertheless, even in a worst-case scenario of renewed conflict and a deepening blockade of Tigray, Western players face the dilemma of needing to avoid turning Ethiopia into an outright pariah. Not only is Ethiopia a strategic partner in a highly unstable region, but broader economic sanctions could heighten the risk of Ethiopia’s disintegration along Yugoslavia lines. For now, there is no credible alternative diplomatic partner to the PP government, especially in a context where most opposition parties represent narrow ethno-nationalistic interests.